发布时间:2020年03月23日 14:09:46 来源:振东健康网

马青变,郑亚安(北京大学第三医院急诊科,北京100191)

中图分类号:R631文献标识码:A文章编号:1008-1070(2017)07-0008-04doi:10.3969/j.issn.1008-1070.2017.07.003

【摘 要】脓毒症是急诊常见的疾病之一,具有发病率高、病死率高、致残率高、医疗花费高等特点,已成为近30年来医学界关注的热点和焦点。随着人们对脓毒症的认识不断加深,脓毒症的定义也不断更新变化。从1990到2016年脓毒症的定义经历了3次变迁,2016年2月欧洲重症医学协会和美国重症医学协会联合发布了脓毒症3.0的定义和相关诊断标准[1]。新标准删除了全身炎症反应综合征(systemicinflammatoryresponsesyndrome,SIRS)和严重脓毒症,将脓毒症定义为机体对感染产生的不适当的宿主反应,从而导致致命的器官功能障碍;脓毒症休克是病死率明显增加的脓毒症之一。

1 脓毒症的病因

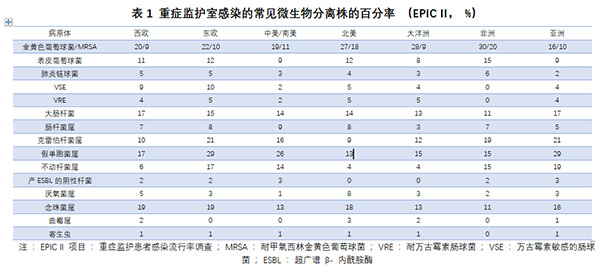

感染是脓毒症的主要病因。EPICII项目(重症监护患者感染流行率调查)研究表明[2]:成人常见的感染部位依次为肺部(64%)、腹腔(20%)、血流(15%)、肾脏和生殖道(14%)。70%的感染患者可以找到病原微生物,分离的菌株中47%为G+菌,阳性菌中金黄色葡萄球菌占到20%;其他还包括62%为G-菌和19%的真菌。儿童脓毒症患者中,常见的感染部位依次为肺部(40%)、血流(19%)、腹腔(9%)、中枢神经系统(4%)和泌尿生殖系统(4%);分离出的菌株中G+占28%,G-占27%,真菌占13%,病毒占21%[3](表1)。上述微生物学数据与当地微生物的培养和检出能力直接相关,因此并不能完全客观地反映微生物的流行病学情况。

此外,脓毒症的致病微生物与感染部位密切相关,如腹腔感染的常见病原微生物为革兰染色阴性菌[4]。脓毒症患者的预后除与感染菌株相关之外,还与患者本身是否存在高危因素相关,血液系统肿瘤、肝硬化、机械通气、肾脏替代治疗、糖皮质激素的应用都可以增加脓毒症患者的住院病死率[5]。

2 脓毒症的抗感染策略

2.1脓毒症/脓毒症休克的早期识别和诊断策略脓毒症/脓毒症休克的早期识别和早期治疗能改善预后、降低脓毒症相关病死率[6-8]。缩短脓毒症/脓毒症休克的诊断时间是降低脓毒症所致多器官功能障碍的病死率的重要手段[9,10]。因此,在急诊对有潜在感染的重症患者需常规进行脓毒症筛查,确定是否发生了严重脓毒症/脓毒症休克。2016年欧洲危重病医学会及美国危重病医学会第三次全身性感染及感染性休克国际共识定义Sepsis-3中建议对可疑感染的患者应用快速序贯性器官衰竭评估(qSOFA)量表来进行脓毒症的初步快速床旁筛查[11]。qSOFA标准包括呼吸频率≥22/min,意识状态改变,收缩压≤100mmHg,每项为1分,累计超过2分高度提示脓毒症,临床医生应积极的对器官功能进行进一步评价[1]。此外,还需对临床表现、感染相关实验室和影像学等进行评估。上述措施有利于早期诊断脓毒症。

2.2脓毒症/脓毒症休克留取感染相关标本的原则和策略临床诊断脓毒症后,无论就诊的场所是急诊还是病房,均应在应用抗菌药物前留取恰当的标本进行需氧瓶、厌氧瓶培养或其他特殊培养。应用抗生素之前留取恰当的标本进行细菌学培养有助于脓毒症的病原学鉴别及抗菌药物方案的确定。由于在首次给予抗菌药物治疗后的几小时内细菌可能被杀死,所以血培养标本必须在应用抗菌药物前抽取。建议同时留取两个或两个以上不同部位的血培养,以提高培养的敏感性。建议留取两套血培养标本,至少一份来自外周血标本,每个血管通路装置内留取一份血标本(48小时内置入的血管通路除外),不同部位的血培养应同时抽取,抽血量应≥10ml[12]。其他如尿、脑脊液、伤口分泌物、呼吸道分泌物或其他可能的感染源标本,也应在抗菌药物应用前留取[13]。特别注意不能因留取标本时间过长而延误抗菌药物治疗的时机。

当感染病原菌的鉴别诊断涉及侵袭性真菌病时,建议采用1,3-β-D葡聚糖检测(G试验)和(或)半乳甘露聚糖检测(GM试验)以及抗甘露聚糖抗体检测作为了解重症患者是否合并系统性真菌感染的快速诊断方法[14-22],这些测试通常可早于标准培养方法为临床提供检测结果,但需排除假阳性结果[23]。

此外,多项研究表明,降钙素原是重症脓毒症患者的早期诊断的有效指标[24],因此建议将降钙素原作为脓毒症的早期诊断指标。

2.3脓毒症/脓毒症休克抗生素的应用策略一旦临床确诊脓毒症/脓毒症休克,尽早静脉应用合理的抗生素至关重要[25,26]。对脓毒性休克患者而言,每延迟1小时应用抗菌药物将增加12%的病死率,无论是否伴有休克,严重脓毒症患者均应尽早应用抗菌药物[27,25,28-35],因此Sepsis3.0建议应在1小时内开始有效的静脉抗菌药物治疗。

急诊是脓毒症患者最常见的初诊场所,限于目前的病原学检测方法,通常医生在采集标本48小时后才可获得检测结果,因此经验性抗生素治疗是难免的。初始经验性抗感染治疗方案应采用覆盖所有可能致病菌包括细菌和(或)真菌等,且在疑似感染源组织内能达到有效浓度的单药或多药联合治疗。如果初始经验性抗感染治疗方案未采取恰当的抗菌药物治疗,将增加严重脓毒症/脓毒性休克的发病率和病死率[25,28,36-42]。脓毒症患者常伴有肝肾功能异常及体内液体异常分布,必要时需检测血药浓度来确保达到有效药物浓度及减少药物毒性[43]。

一旦病原学明确应考虑降阶梯治疗策略。研究结果表明,抗菌药物的降阶梯治疗能降低病死率[44,45];与延续经验性治疗相比,采用经验性抗菌治疗基础上的降阶梯抗菌药物策略的脓毒症患者病死率降低,ICU住院时间相当[46],因此推荐一旦有明确病原学依据应考虑降阶梯治疗策略。

脓毒症患者抗菌药物的应用、更换和停用均应依据临床医师的判断及患者的临床情况而定,一般情况下建议抗菌药物的疗程为7~10天[47],但对临床反应缓慢、感染灶难以充分引流和(或)合并免疫缺陷者可适当延长疗程[48,49]。如粒细胞缺乏患者并发脓毒症时,用药时间可适当延长;如存在深部组织感染及血流感染超过72小时的粒细胞缺乏患者,抗菌药物的疗程需延长至>4周或至病灶愈合、症状消失[48]。

对疑似或确诊流感、严重流感引起的脓毒症,早期应用抗病毒治疗有可能降低病死率[50-54]。常用抗病毒药物为神经氨酸酶抑制剂(奥司他韦或扎那米韦)。研究表明,双倍剂量的奥司他韦治疗流感所致脓毒症未显示出优越性,建议应用常规剂量治疗[55]。

对可能有特定感染源(如坏死性软组织感染、腹腔感染、导管相关性血流感染)的脓毒症患者,应尽快明确其感染源[56],并尽快采取恰当的感染源控制措施。研究结果显示,脓毒症感染源控制原则包括感染源的早期诊断和及时处理(特别是脓肿引流、感染坏死组织清创、处理可能感染的装置等);对可以通过手术或引流等方法清除的感染灶,包括腹腔内脓肿、胃肠道穿孔、胆管炎、肾盂肾炎、肠缺血、坏死性软组织感染和其他深部间隙感染(如脓胸或严重的关节内感染),均应尽快清除[57];如考虑感染源为血管通路,应尽快拔除导管[58,59]。

参考文献:

[1]Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (sepsis-3) [J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8):801-810.

[2]Vincent J L, Rello J, Marshall J, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units[J]. JAMA, 2009, 302(21):2323.

[3]Weiss S L, Fitzgerald J C, Pappachan J, et al. Global epidemiology of pediatric severe sepsis: the sepsis prevalence, outcomes, and therapies study[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2015, 191(10): 1147-1157.

[4]De WJ, Lipman J, Sakr Y, et al. Abdominal infections in the intensive care unit: characteristics, treatment and determinants of outcome[J]. BMC Infectious Diseases, 2014, 14(1):420.

[5]Hartman ME, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, et al. Trends in the epidemiology of pediatric severe sepsis[J]. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2013, 14(7):686-693.

[6]De PN, Dreyfuss D. How to prevent ventilator-induced lung injury [J]. Minerva Anestesiologica, 2012, 78(9):1054-1066.

[7]Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2010, 36(2):222-231.

[8]Moore LJ, Moore FA. Early diagnosis and evidence-based care of surgical sepsis [J]. J Intensive Care Med, 2013, 28(2):107-117.

[9]Jansen TC, Van BJ, Schoonderbeek FJ, et al. Early lactate-guided therapy in intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2010, 182(6):752-761.

[10]Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, et al. Lactate clearance vs central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA, 2010, 303(8):739-746.

[11]Abraham E. New definitions for sepsis and septic shock: continuing evolution but with much still to be done[J]. JAMA, 2016, 315(8):757.

[12]Mermel LA, Maki DG. Detection of bacteremia in adults: consequences of culturing an inadequate volume of blood[J]. Ann Intern Med,1993, 119(4):270-272.

[13]Weinstein MP, Murphy JR, Reller LB, et al. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures: a comprehensive analysis of 500 episodes of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. II. Clinical observations, with special reference to factors influencing prognosis[J]. Rev Infect Dis, 1983, 5(1):54.

[14]Hanson KE, Pfeiffer CD, Lease ED, et al. β-D-glucan surveillance with preemptive anidulafungin for invasivecandidiasis in intensive care unit patients: a randomized pilot study[J]. Plos One, 2012, 7(8): e42282.

[15]León C, Ruizsantana S, Saavedra P, et al. Value of β-D-glucan and Candida albicans germ tube antibody for discriminating between Candida colonization and invasive candidiasis in patients with severe abdominal conditions[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2012, 38(8):1315-1325.

[16]Lamoth F, Cruciani M, Mengoli C, et al. β-Glucan antigenemia assay for the diagnosis of invasive fungal infections in patients with hematological malignancies: a systematic review and meta?analysis of cohort studies from the Third European Conference on Infections in Leukemia (ECIL-3)[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2012, 54(5):633-643.

[17]Onishi A, Sugiyama D, Kogata Y, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serum 1,3-beta-D-glucan for pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, invasive candidiasis, and invasive aspergillosis: systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. J Clin Microbiol 2012, 50(1):7-15.

[18]Alam FF, Mustafa AS, Khan ZU. Comparative evaluation of (1, 3)-β-D-glucan, mannan and anti-mannan antibodies, and Candida, species-specific snPCR in patients with candidemia[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2007, 7(1):103.

[19]Oliveri S, Trovato L, Betta P, et al. Experience with the Platelia Candida ELISA for the diagnosis of invasive candidosis in neonatal patients[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2008, 14(4):391-393.

[20]Sendid B, Poirot JL, Tabouret M, et al. Combined detection of mannanaemia and antimannan antibodies as a strategy for the diagnosis of systemic infection caused by pathogenic Candida species[J]. J Med Microbiol, 2002, 51(5):433-442.

[21]Sendid B, Jouault T, Coudriau R, et al.Increased sensitivity of

mannanemia detection tests by joint detection of alpha and betalinked oligomannosides during experimental and human systemic candidiasis[J]. J Clin Microbiol 2004, 42(1):164-171.

[22]Sendid B, Dotan N, Nseir S, et al. Antibodies against Glucan, Chitin, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Mannan as New Biomarkers of Candida albicans Infection That Complement Tests Based on C. albicans Mannan[J]. Clin Vaccine Immunol Cvi, 2008, 15(12):1868-1877.

[23]Yera H, Sendid B, Francois N, et al. Contribution of serological tests and blood culture to the early diagnosis of systemic candidiasis[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2001, 20(12):864.

[24]Wacker C, Prkno A, Brunkhorst FM, et al. Procalcitonin as a diagnostic marker for sepsis: a systematic review and meta?analysis[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2013, 13(5):426-435.

[25]Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock[J]. Crit Care Med, 2006, 34(6):1589-1596.

[26]Morrell M, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH. Delaying the Empiric Treatment of Candida Bloodstream Infection until Positive Blood Culture Results Are Obtained: a Potential Risk Factor for Hospital

Mortality[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2005, 49(9):3640-3645.

[27]Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2010, 36(2):222-231.

[28]Barie PS, Hydo LJ, Shou J, et al. Influence of antibiotic therapy on mortality of critical surgical illness caused or complicated by infection[J]. Surg Infect, 2005, 6(1):41-54.

[29]Castellanosortega á, Suberviola B, Garcíaastudillo LA, et al. Impact of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign protocols on hospital length of stay and mortality in septic shock patients: results of a three-year follow-up quasi-experimental study[J]. Crit Care Med, 2010, 39(4):1036-1043.

[30]Puskarich MA, Trzeciak S, Shapiro NI, et al. Association between timing of antibiotic administration and mortality from septic shock in patients treated with a quantitative resuscitation protocol[J]. Crit Care Med, 2011, 39(9):2066-2071.

[31]El Solh AA, Akinnusi ME, Alsawalha LN, et al. Outcome of septic shock in older adults after implementation of the sepsis “bundle”[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2008, 56(2):272-278.

[32]Gurnani PK, Patel GP, Crank CW, et al. Impact of the implementation of a sepsis protocol for the management of fluid-refractory septic shock: A single-center, before-and-after study [J]. Clin Ther, 2010, 32(7):1285-1293.

[33]Barochia AV, Cui XZ, Vitberg D, et al. Bundled care for septic shock: an analysis of clinical trials[J]. Crit Care Med, 2010, 38(2): 668-678.

[34]Ferrer R, Artigas A, Suarez D, et al. Effectiveness of treatments for severe sepsis: A prospective, multicenter, observational study[J]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2009, 180(9):861-866.

[35]Ferrer R, Martin-Loeches I, Phillips G, et al. Empiric antibiotic treatment reduces mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock from the first hour: results from a guideline-based performance improvement program[J]. Crit Care Med, 2014, 42(8):1749-1755.

[36]Leibovici L, Shraga I, Drucker M, et al. The benefit of appropriate empirical antibiotic treatment in patients with bloodstream infection[J]. J Intern Med, 1998, 244(5):379-386

[37]brahim EH, Sherman G, Ward S, et al. The influence of inadequate antimicrobial treatment of bloodstream infections on patient outcomes in the ICU setting[J]. Chest, 2000, 118(1):146-155.

[38]Lee CC, Lee CH, Chuang MC, et al. Impact of inappropriate empirical antibiotic therapy on outcome of bacteremic adults visiting the ED[J]. Am J Emerg Med, 2012, 30(8):1447-1456.

[39]Lee CC, Chang CM, Hong MY, et al. Different impact of the appropriateness of empirical antibiotics for bacteremia among younger adults and the elderly in the ED[J]. Am J Emerg Med, 2013, 31(2):282-290.

[40]Ruizgiardin JM, Jimenez BC, Martin RM, et al. Clinical diagnostic accuracy of suspected sources of bacteremia and its effect on mortality[J]. Eur J Intern Med, 2013, 24(6):541-545.

[41]Retamar P, Portillo MM, Lópezprieto MD, et al. Impact of Inadequate Empirical Therapy on the Mortality of Patients with Bloodstream Infections: a Propensity Score-Based Analysis[J].

Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2012, 56(1):472.

[42]Chen HC, Lin WL, Lin CC, et al. Outcome of inadequate empirical antibiotic therapy in emergency department patients with community-onset bloodstream infections[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2013, 68(4):947-953.

[43]Ali MZ, Goetz MB. A Meta-Analysis of the Relative Efficacy and Toxicity of Single Daily Dosing Versus Multiple Daily Dosing of Aminoglycosides[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 1997, 24(5):796-809.

[44]Garnacho-Montero J, Gutiérrez-Pizarraya A, Escoresca-Ortega A et al (2014) De-escalation of empirical therapy is associated with lower mortality in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock[J]. Intensive Care Med, 40:32-40.

[45]Gomes Silva BN, Andriolo RB, Atallah AN, et al. De-escalation of antimicrobial treatment for adults with sepsis, severe sepsis or septic shock[J]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2010, 12(12):CD007934.

[46]Leone M, Bechis C, Baumstarck K, et al. De-escalation versus continuation of empirical antimicrobial treatment in severe sepsis: a multicenter non-blinded randomized noninferiority trial[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2014, 40(10):1399-1408.

[47]Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign Campaign:International Guidelines for Management of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock[J]. Crit Care Med, 2013, 41: 580-637.

[48]中华医学会血液学分会.中国中性粒细胞缺乏伴发热患者抗菌药物临床应用指南(2016年版)[J].中华血液学杂志,2016,33(5):693-696.

[49]Freifeld AG, Bow EJ, Sepkowitz KA, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer: 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2011, 52(4):427-431.

[50]Muthuri SG, Venkatesan S, Myles PR, et al. Impact of neuraminidase inhibitors on influenza A(H1N1)pdm09-related pneumonia: an individual participant data meta-analysis[J]. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2016, 10(3):192.

[51]Gao HN, Lu HZ, Cao B, et al. Clinical findings in 111 cases of influenza A (H7N9) virus infection[J]. N Engl J Med, 2013, 368(24):2277-2285.

[52]Poeppl W, Hell M, Herkner H, et al. Clinical aspects of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in Austria[J]. Infection, 2011, 39(4):341-352.

[53]Jain S, Kamimoto L, Bramley AM, et al. Hospitalized patients with 2009 HINI influenza in the United States, April-June 2009[J].N End J Med, 2009, 36l(20):1935-1944.

[54]Writing Committee of the WHO Consultation on Clinical Aspects of Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza, Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T, et al. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection[J]. N Engl J Med, 2010, 362(18):1708.

[55]South East Asia Infectious Disease Clinical Research Network. Effect of double dose oseltamivir on clinical and virological

outcomes in children and adults admitted to hospital with severe influenza: double blind randomised controlled trial[J]. BMJ, 2013, 346:f3039.

[56]Jimenez MF, Marshall JC. Source contml in the management of sepsis[J]. Intensive Care Med,2001, 27(suppl 1):S49-S62.

[57]Boyer A, Vargas F, Coste F, et al. Influence of surgical treatment timing on mortality from necrotizing soft tissue infections requiring intensive care management[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2009,

35(5):847-853.

[58]O’Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections[J]. Am J Infect Control, 2011, 39(4 Suppl 1):S1-S34

[59]Miller DL, O’Grady NP. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections: recommendations relevant to interventional radiology for venous catheter placement and maintenance[J]. J Vasc Interv Radiol, 2012, 23(8):997-1007.